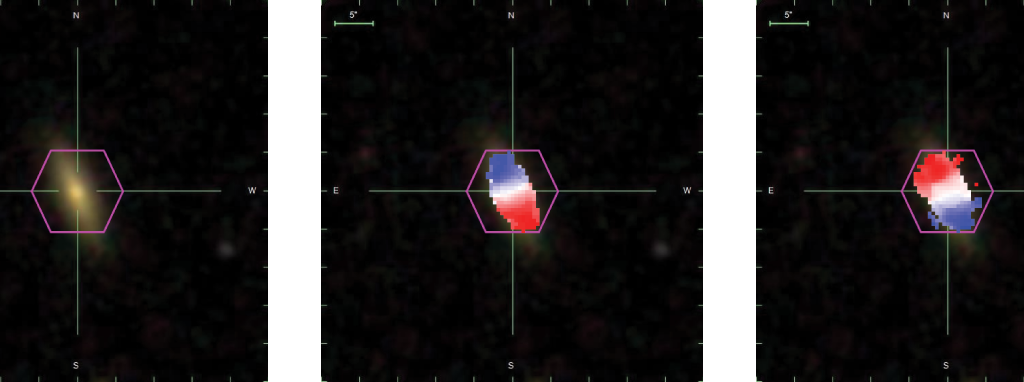

Phoenix – Astronomers have discovered that many small galaxies hosting active supermassive black holes have their stars and gas spinning out of sync – sometimes in completely opposite directions.

Separate images for download: sky | stars | gas

Image Credit: Dominic Schwein and the SDSS collaboration

“Our research suggests that black holes can reshape entire galaxies, not just their centers,” says Dominic Schwein of Colorado College, lead author of the study.

The results, presented today at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, come from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS). The SDSS is an ongoing survey that for nearly 30 years has been making a map of the Universe, from nearby asteroids to the most distant quasars all the way across the Universe. The SDSS’s MaNGA component survey (MApping Nearby Galaxies at Apache point observatory) has looked in detail at thousands of nearby galaxies, mapping the internal motions of each galaxy as traced by both stars and by the hydrogen gas between the stars.

In most galaxies, stars and gas share a common spin, inherited from the gas cloud from which the galaxy formed. But in some galaxies, the gas and stars spin at different angles and sometimes even in completely opposite directions. Various explanations have been suggested for the mismatch, from galactic mergers to gas transfer from other galaxies to “active galactic nuclei (AGN)” – the bright, energetic galaxy centers powered by matter falling into supermassive black holes.

Schwein and colleagues investigated the hypothesis that AGN are responsible. They looked in detail at 94 small galaxies seen by the SDSS’s MaNGA survey, each of which had a suspected AGN at its center.

Image Credit: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

“We were surprised by how often the spins didn’t line up,” says Catherine Witherspoon, a professor at Colorado College who advises Schwein as part of the research team. “Among similar low-mass galaxies without an active black hole, about a quarter show counter-rotation. With an AGN, that fraction jumps to roughly half. That’s a big signal that something powerful is happening.”

The team wrote Python code to find the axis of rotation of the stars, and also of the hydrogen gas. For each galaxy, they find the angle of offset between the two axes between zero (perfectly matched) and 180 degrees (completely opposite directions). They define a galaxy as counter-rotating when the two axes of rotation differ by more than 90 degrees. Lastly, they compared the results for their 94 galaxies to more than 3,000 galaxies observed by MaNGA. Across the board, galaxies with AGN are more likely to show significant offsets between stars and gas than galaxies without AGN.

Contacts

Dominic Schwein

Colorado College

d_schwein@coloradocollege.edu

Catherine Witherspoon

Colorado College

cwitherspo2023@ColoradoCollege.edu

Dhanesh Krishnarao

Colorado College

dkrishnarao@coloradocollege.edu

Keith Hawkins

Director, After Sloan 5 (AS5) Collaboration

University of Texas at Austin

keithhawkins@utexas.edu

The most likely explanation for this observation is AGN feedback: energetic outflows powered by the central black hole blow gas out from the galaxy’s core, which later falls back at a different angle relative to the stars, which remain in the same place.

“Active black holes are not just lighting up the centers; they can stir up a galaxy’s gas on much larger scales,” said co-author Dhanesh Krishnarao. “If that’s what we’re seeing here, it means AGN play a bigger role in shaping the life histories of small galaxies than we’ve appreciated.”

Next, the researchers plan to test whether these rotational offsets are tied to other galaxy traits, such as metallicity, star formation histories, and other stellar population properties, and to explore whether similar trends hold in more massive galaxies.

With the current generation of SDSS (SDSS-V) expected to end observations in 2027, the SDSS collaboration is planning next steps. The proposed After Sloan 5 (AS5) project will extend the capabilities of the current survey.

The full AS5 program will transform our understanding of the dynamic Universe from quasars to stellar transients with spectroscopic followup of photometrically varying sources (through the Dynamic Universe Explorer), investigate the chemistry and dynamics of the Milky Way’s distant, unexplored regions (through the Hidden Galaxy Explorer), map stars and gas at star-formation scales across Local Group galaxies (through the Local Group Explorer), and probe the key nucleosynthetic pathways that produce the elements on the periodic table with high precision stellar abundances (through the Atomic Genesis Explorer).

“Data from AS5 will dramatically improve our understanding of the galaxies, AGN, and so many other areas of astronomy,” says Keith Hawkins of the University of Texas at Austin, Director of the AS5 project.

For now, the message is clear: even in the smallest galaxies, black holes can pack a big punch.

About the SDSS

Funding for the Sloan Digital Sky Survey V has been provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Heising-Simons Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and the Participating Institutions. SDSS acknowledges support and resources from the Center for High-Performance Computing at the University of Utah. SDSS telescopes are located at Apache Point Observatory, funded by the Astrophysical Research Consortium and operated by New Mexico State University, and at Las Campanas Observatory, operated by the Carnegie Institution for Science. The SDSS web site is www.sdss.org.

SDSS is managed by the Astrophysical Research Consortium for the Participating Institutions of the SDSS Collaboration, including Caltech, the Carnegie Institution for Science, Chilean National Time Allocation Committee (CNTAC) ratified researchers, The Flatiron Institute, the Gotham Participation Group, Harvard University, Heidelberg University, The Johns Hopkins University, L’Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Leibniz-Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam (AIP), Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie (MPIA Heidelberg), Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik (MPE), Nanjing University, National Astronomical Observatories of China (NAOC), New Mexico State University, The Ohio State University, Pennsylvania State University, Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), the Stellar Astrophysics Participation Group, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, University of Arizona, University of Colorado Boulder, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, University of Toronto, University of Utah, University of Virginia, Yale University, and Yunnan University.